15 years ago today: what you weren't told about the bailout

On 8 October 2008, the UK government announced something seismic. There was also quite a lot that wasn't announced - evidence of a state-led, international drive to manipulate interest rates...

Exactly 15 years ago today was a shocking day at the height of the global financial crisis. On 8 October 2008, Gordon Brown announed three huge government schemes to try to stop the financial system seizing up, including £50bn to bail out the UK’s banks from the consequences of their own top bosses’ gross mismanagement. They’d lent far too much in the Noughties, reaping bigger bonuses the more they lent; then when they realised huge sums would never be repaid, they suddenly stopped lending - making cash scarce. The cost of cash rocketed, particularly after George Bush’s outgoing administration decided to let Lehman Brothers go under on 15 September. Soaring interest rates threatened to turn a banking crisis into a depression.

In the three weeks that had gone by since then, the system hadn’t steadied itself. Libor, the key measure of the real cost of borrowing cash, upon which millions of loans worth trillions of dollars were based, was far too low to reflect the real interest rates banks were paying to get hold of much-needed cash from the few lenders out there. Most banks were lying, understating the interest rates they’d really have to pay, which produced a false, understated Libor average. But it was still far too high for policy-holders in Downing Street and the Treasury, who were desperate to get Libor down so they could show the world their crisis measures were working.

Libor (just like its Euro equivalent, Euribor) was like a thermometer that measured the temperature of the economic patient, which kept on giving out unwelcome readings suggesting the medicine wasn’t working. So - should governments and central banks try and get their patient’s temperature down by administering more financial medicine in the form of government loan guarantee schemes - schemes that so far hadn’t worked to make borrowing cheaper? Or should they tamper with the thermometer in the hope that a better reading, albeit artificial - aka false - might restore confidence?

The evidence suggesting they did the latter has been covered it up from the public, including Parliament and Congress. It’s laid out in Rigged and on my newly updated timeline on Substack. Some evidence emerged in the trials and some in leaks of documents and audio. What it shows very clearly is evidence that it wasn’t just the UK government and the Bank of England who got involved in trying to get Libor and/or Euribor down. It was also the Banque de France, Banca d’Italia, Banco de España, the European Central Bank and also the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (They’ve all been invited to respond; none commented except the ECB, which didn’t touch on the detailed evidence but said it ‘strongly rebutted’ the assertions put to it).

On 8 October, not only did Gordon Brown announce £50bn to bail out UK banks. The action being taken, as he kept saying, had to be ‘global’ and ‘co-ordinated’. He and his staff were talking to central banks across the world and also to world leaders. Six central banks across announced cuts that day in their official rates to try to ease the crisis by making money cheaper to borrow and lend. The trouble was that ever since the credit crunch began in August 2007, central banks no longer had effective control over interet rates. They could cut rates all they liked and the banks, still frozen in terror over how much money they and their counterparties might have lost, still weren’t ready to lend - so the real cost of cash (measured by Libor and Euribor) wouldn’t come down. Or at least, they wouldn’t if the banks were telling the truth about how much they were really paying to get hold of funds on international markets.

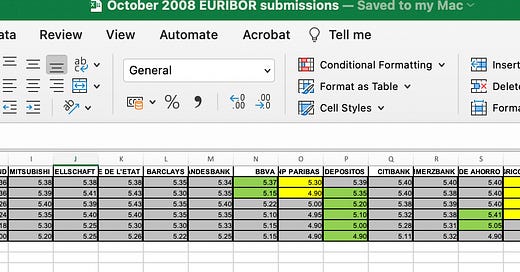

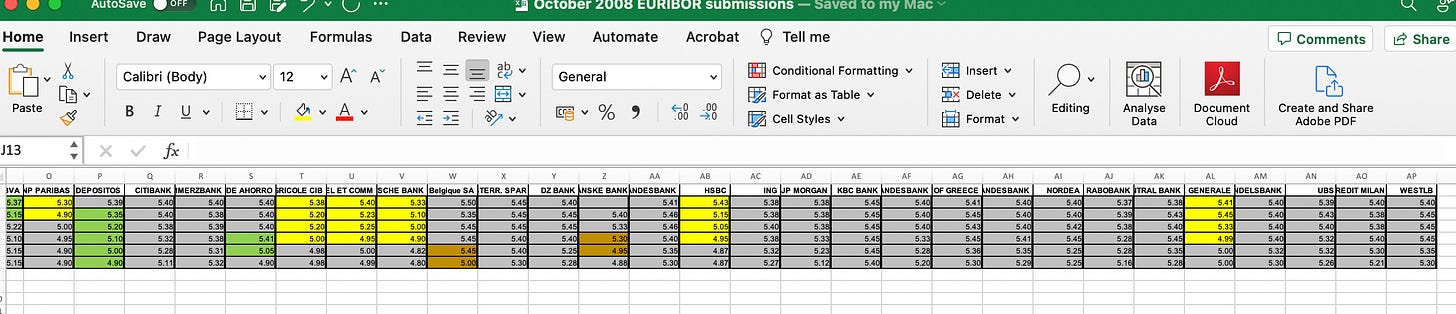

The following chart, just added to the timeline, shows in yellow how, in the days immediately following the 8 October, the French banks dropped their estimates of the interest rates they had to pay to borrow euros, which were averaged to get the Euribor index of the cost of borrowing euros. They did so in unison along national lines - dropping them over 3-4 days by record amounts (30-40 basis points - more than after 11 September 2001). Note this is an international market for borrowing and lending cash that knows no national boundaries. In a pan-European market for borrowing and lending euros, any significant market-moving news would affect all banks borrowing and lending euros. Yet this was clearly not the market at work here. It was happening along national lines. Because of the ECB’s federal structure, the only entities legally empowered to order commercial banks to drop their Euribor estimates were the national central banks - in the French case, Banque de France. The Spanish banks (in green) weren’t far behind, followed closely by the Italians. Some of them dropped their rates after 8 October. Others fell into line after the following weekend, after Brown flew to Paris to meet Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet and then EU president José-Manuel Barroso. However, the banks of other countries, such as Germany, didn’t fall in line - proving that these movements were driven by national, rather than pan-market factors.

As Brown flew to Paris, UK banks were urging each other to drop their Libor rates. Barclays, whose dollar cash trader Peter Johnson had been swimming hard against the tide for more than a year to try and publish Libor rates that honestly reflected what he was paying to borrow cash, was the odd man out. His colleague Pete Spence, the sterling cash trader, was trying to do the same. Johnson’s boss Mark Dearlove got a call from a top executive at RBS telling him Barclays should drop its Libor rates because it was ‘spoiling it for everyone else’. That wouldn’t be the only call he would get from on high before the month was out. (Gordon Brown has repeatedly been asked to comment on these matters and has repeatedly declined).

This evidence of international, state-led intervention in the setting of Libor and Euribor to drive them down to artificially low levels was kept out out of regulators’ notices fining banks billions of dollars for rigging interest rates. It’s only because of leaked audio and documents that the public has a clue about this secret history - of a real manipulation ordered from the top - as opposed to the ‘rigging’ by traders that the US courts have now decided wasn’t illegal - or even against any rules. You can read all about it in Rigged and check the previously suppressed evidence, now exhibited here.

Next time… the phone call that made the US Deparment of Justice pounce - only to keep it from the US public.